UCI Cyber-physical Security Researchers Highlight Vulnerability of Solar Inverters

Device hidden in a coffee cup could destabilize the power grid, triggering a blackout

Aug. 18, 2020 - Cyber-physical systems security researchers at the University of California, Irvine can disrupt the functioning of a power grid using about $50 worth of equipment tucked inside a disposable coffee cup.

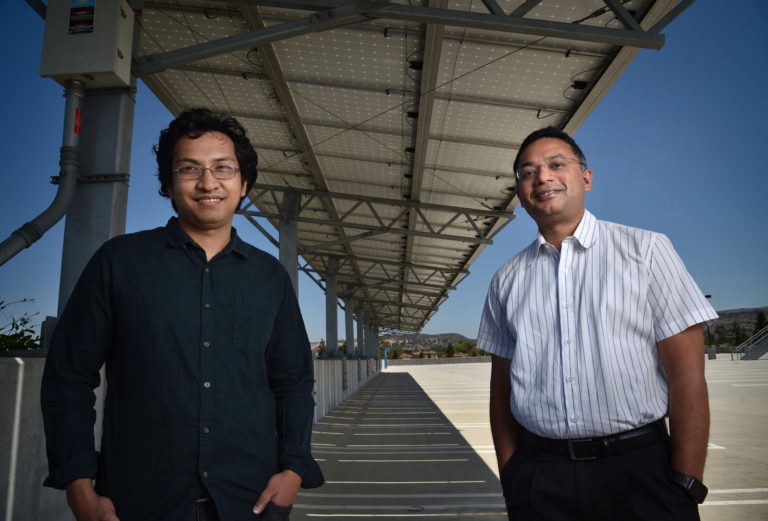

In a presentation delivered at the recent Usenix Security 2020 conference, Mohammad Al Faruque, UCI associate professor of electrical engineering & computer science, and his team revealed that the spoofing mechanism can generate a 32 percent change in output voltage, a 200 percent increase in low-frequency harmonics power and a 250 percent boost in real power from a solar inverter.

Al Faruque’s group in UCI’s Henry Samueli School of Engineering have made a habit in recent years of finding exploitable loopholes in systems that combine computer hardware and software with machines and other infrastructure. In addition to heightening awareness about these vulnerabilities, they invent new technologies that are better shielded against attacks.

For this project, Al Faruque and his team used a remote spoofing device to target electromagnetic components found in many grid-tied solar inverters.

“Without touching the solar inverter, without even getting close to it, I can just place a coffee cup nearby and then leave and go anywhere in the world, from which I can destabilize the grid,” Al Faruque said. “In an extreme case, I can even create a blackout.”

Solar inverters convert power collected by rooftop panels from direct to alternating current for use in homes and businesses. Often, the sustainably generated electricity will go into microgrids and main power networks. Many inverters rely on Hall sensors, devices that measure the strength of a magnetic field and are based on a technology that originated in 1879.

It’s this relatively ancient gizmo that makes many cyber-physical properties vulnerable to attack, Al Faruque said. Beyond solar inverters, Hall sensors can be found in cars, freight and passenger trains, and medical devices, among other applications.

The spoofing apparatus assembled by Al Faruque’s team consists of an electromagnet, an Arduino Uno microprocessor, and an ultrasonic sensor to measure the distance between the unit and the solar inverter. A Zigbee network appliance is used to control the mechanism within a range of about 100 meters, but that can be replaced by a Wi-Fi router that would enable remote operation from anywhere on the planet.

Anomadarshi Barua, a second-year Ph.D. student in electrical engineering & computer science who led the development of this technique, said that the components of the spoofing device are so simple and straightforward that a high school student could construct it.

“Schools all around the world teach kids how to program an Arduino processor,” he said. “Even UCI has camps that teach this technology. However, they would need a little more advanced knowledge to figure out the control part of the system.”

Barua noted that such an attack could target an individual home or an entire grid. “You could use the device to shut down a shopping mall, an airport or a military installation,” he said.

For Al Faruque, this endeavor – supported by a smart grid security program under the University of California Office of the President – points out gaps in older technologies that even seasoned experts may have overlooked. His group recently received funding from the National Science Foundation to start a project in September centered on building new, more secure Hall sensors that can’t be foiled by a cleverly placed coffee cup.

– Brian Bell